Research > Syntheses > “MOVESCI: Adaptive Toolbox”

Climbing is frequently suggested to be a “skill-based sport.” If this is true, what would a skill-based progression look like? Below is a framework that could help climbers better “program” skills in a way similar to how physical trainers or coaches of more traditional sports periodize or block their training.

The Periodization of Skill Training — or “POST” — Framework is an approach proposed by Otte, Millar, and Klatt in 2019. Very simply, the POST framework suggests that different amounts of complexity, (in)stability, and training-representativeness may be employed to better take an evidence-informed approach to the following skill development stages: (1) coordination training, (2) skill adaptation training, and (3) performance training.

POST Framework Quick History (click to expand)

The POST Framework was built as an extension of Farrow and Robertson’s 2017 Skill Acquisition Periodization — or “SAP” — framework as well as the broader literature on the Constraints-led Approach (Newell, 1986; Davids, 2005) or CLA.

The framework is intended to be used by what the authors term “specialist coaches” -specifically those focused on individual or small-group training. The goal being to offer that “extra” improvement or refinement that many athletes feel they need outside of their main team training. It should be noted that team training is an important component in its own right involving the relatedness component of motivation that many independent athletes miss.

| Key Concept | Description | Tenets |

| Representativeness | Closeness of Skill Training to Performance | (i) guide toward relevant opportunities for action with environment; (ii) integrate motor technique with decision and awareness; (iii) design relevant training |

| Stability / Instability | Consistency vs. Adaptability | (i) be consistent under challenge, and adapt to exploit fluctuating circumstances; (ii) achieve the same task-goal in different ways, and use the same solution for different problems. |

| Information or Task Complexity | Amount of Information to Control Process | (i) challenge relationship of action and perception; (ii) individualize movement, exploration, interaction; (iii) highlight, disguise, or express perceptual information; (iv) manipulate controllable factors for different ability. |

The authors also recommend specialist coaches use specific tools to manage information complexity, namely: task and equipment modification, and the practice schedule. See here from the authors’ own words:

“Alongside manipulating commonly advocated task constraints, such as instruction, rule changes, or playing area and surface adjustments (Correia et al., 2019), benefits of modifying equipment for the management of informational complexity are proposed. In particular, the removal or addition of perceptual information is considered to support or challenge athletes’ exploration for functional perception-action couplings and movement solutions (Davids et al., 2008; Renshaw and Chow, 2019).”

— Otte, Millar, & Klatt (2019)

Stage 1: Coordination Training

Next, let’s look at the different stages and begin the climbing-specific examples. Coordination training (Stage 1) keeps the environment simple, with minimal changes, and complexity low. The goal is to build stability. Let’s use the example of t-nuts. I’ll use this example because it’s a skill that some people use a lot, and others don’t use at all.

This seems like a great time to be mindful of t-nut holes. Walking on volumes. Trying not to slip. Try and press some rubber into a t-nut to get a tiny vector of force going perpendicular to the rim of a t-nut hole.

Jason Chang (@theshortbeta)

In climbing, let’s say we want to train the use of a shoe in a t-nut (the little hole in the wall used to attach a hold) on the wall, we might provide a climber with a slab / vertical wall and 1 climb with large handholds spaced in a very predictable “ladder” formation and using large handholds. We might have the athlete try their climb with the simple rule: “you have to use a t-nut for your lower foot on every hand move, it has to be the opposite foot as the hand you’re moving.” We should also keep task complexity low by giving them only a very small window of T-nuts to use. Then we have them repeat the climb a few times. Perhaps we add one small progression here, like reducing the size of the hands or feet, but then move to a new problem to avoid boredom. Once they appear to have some consistency here across a few sessions, we’ll move them to the main stage: the skill adaptability stage.

Stage 2, Phase 1: Movement Variability Training

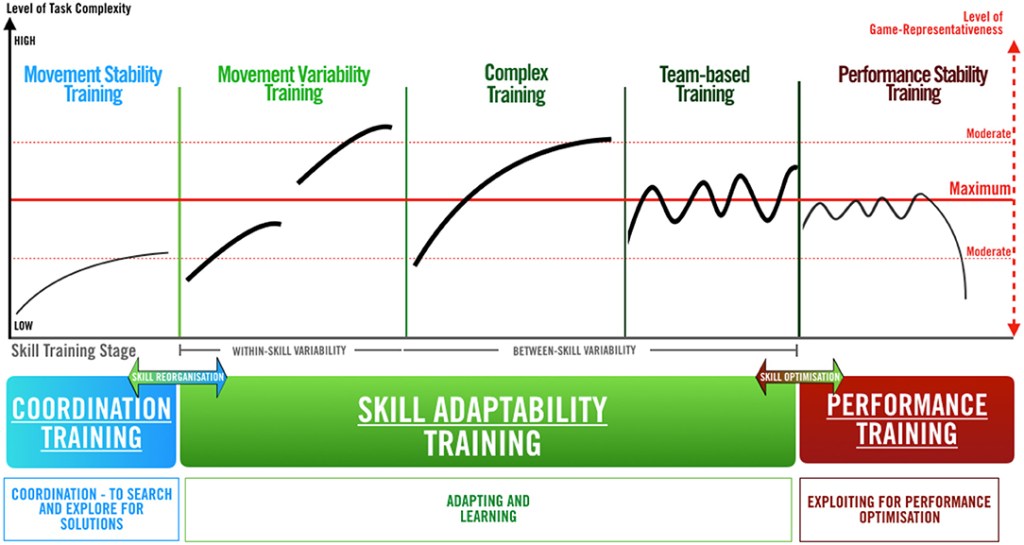

The skill adaptability stage is the main stage for the POST framework. It includes Movement Variability Training, Complex Training, and Team-based Training. And the goal here is adaptability, functionality, and the ability to respond to dynamic, changing environments. See below for a graphical depiction of the overall framework.

The skill training progression (left-to-right) is on the x-axis, while we have two y-axes: Level of Task Complexity (Left y-axis) and Level of Game Representativeness (Right y-axis). Additionally, within the Movement Variability Training Phase we have two sub-phases, the first where task complexity and the level of game representativeness increase from lower-to-higher, and a second where complexity rises but game-representativeness actually decreases. The major goal here — adaptation, functionality, and response to changing environments — should be trained by interfering (in small, careful ways) with a climber’s perception and movement, largely through variation. See below for how variation is defined by the authors:

Due to this paper’s primary focus on “specialist coaching” at the performance level (i.e., focused on skill refinement of complex skills executed by athletes in team sports), two distinct practice schedule arrangements are considered: “within-skill variability” (i.e., “discernible variation in the execution of the same skill”); and “between-skill variability” (i.e., “switching of skills during practice”; see Buszard et al., 2017, p. 2).

Otte, Millar, & Klatt (2019)

In our example of t-nut use, we would start exploring variable use of the t-nuts as we increase the level of task complexity and the level of game representativeness. Below is a table using both (a) the level of task complexity and game of representativeness from the POST framework, as well as (b) the modifiable factors of the task, environment, and individual using a separate (but related) framework called the Constraints-led Approach (CLA). We’ll call this the t-nut table.

| Factor | Level of Task Complexity | Level of Game Representativeness |

| Task: Rainbow Hands | Ladder Hands to increasing v-grade difficulty. | Pick more competition-based holds. |

| Task: Which Foot / Hand | Which Foot is higher during reach ; which hand are you reaching with | —- |

| Task: Time | Increase / decrease time for planning before climbing | Reduce Time to competition-based needs |

| Task: Equipment | Rounded vs. pointed shoes; vision constraining glasses; tape placed over (or partially over) the t-nut | Ideal Shoe change-up during Competition ; change size of t-nut to volume holes. |

| Individual: Mobility | Near End Range-of-Motion (hip flexor, ankle dorsiflexion, hip abduction, hip internal / external rotation) t-nut choice | —- |

| Individual: Motivation | Stories; Emotions; building buy-in | Rewards; Competition between two individuals / teams |

| Individual: “intrinsic dynamics” | Joint-based movements; cadence, velocity, or acceleration habits | Gamify the right “angle-of-pressure / attack” on the T-nut by changing starting position. Gamify using partners, teams, and/or “add-on” or “horse”. |

| Environment: T-nut | Coach chosen to Athlete / Partner chosen | Repetition of alternative t-nuts | Use of different types (e.g. wall vs. volume) |

| Environment: Wall Angle | -5° to +15° Wall Angle | Switch up the wall angle (and required use) under pressure. |

| Environment: Setting | Setting modifications during training | Intentional Forced Setting |

Further, a coach can use tools like:

- “amplification” such as a laser pointer, chalk, teammate, tape, etc.

- “feedback” — to influence an athlete’s perception of whether a t-nut is a viable choice, and action potential on how to use it.

- “traditional repetition vs repetition-without-repetition” approaches. To vary the skill, we can:

- Use the CLA approach in the table above,

- change speed of movement, and

- use a process called differential learning (see further resources) — the use of relatively random but small signal-to-noise-based cues (increase the individual’s specific movement ‘signal’ by amplifying small amounts of ‘noise’ using small changes) that induce positive types of interference between the climber and the climb.

- Finally, many of the teaching approaches coaches use should adjust how an athlete perceives information sources.

Stage 2, Phase 2: Complex Training

Now we want to shift to Complex Training as our next training phase, and the key here is in exploring alternative movement tasks. However, these alternative movement tasks are defined differently depending on whether they are above or below the RED line of maximum game representativeness.

- BELOW the Red Line: structural similarities to our primary skill.

- ABOVE the Red Line:

- Chaining an unrelated movement solution (from the previous move) into your primary skill.

- Increasing the intensity / difficulty of the skill.

- Pre-fatiguing prior to the primary skill.

- Dialing up stress (time, competitors, etc.) prior to execution.

- Attempting to accomplish the task goal with structurally dissimilar movement solutions.

- UPDATE (1/12): A simple heuristic discussed with Dr. Rob Gray (ASU) is to think of the “closeness” of the skill as a continuum. In other words, that we can start with skills that are closer in structure and shift to less related skills.

So what are both similar structural, as well as distinct, solutions which accomplish the same goal as the use of a t-nut? We may need to take a step back and ask “Why would someone ever want to use a t-nut?” One particular pattern I see is a climber (often a shorter one) struggling to generate off their back- or lower-foot — it creates too much elongation. As a result, they may “pop” their lower foot up to increase the amount of drive. Other times I see a problem with timing or accuracy of the move, so missing the hand or having the hips jack-knife away from the wall. In that case, finding a higher footchip for the lower back foot may increase stability for the purpose of spatial timing and/or accuracy.

Occasionally, the only usable foot is so low that the climber looks for a t-nut solution for the upper foot. In this case, they may be able to transfer energy from a lower foot to an upper foot. This could increase the length-of-time during which they have lower-body pressure — and/or raise the center-of-mass — while making limited use of some kind of base, however sub-optimal.

Given this description, what are our alternative solutions that could stand in place of a t-nut? Let’s set our “closer” (more related) alternative solution as an actively flagged foot / smear into the wall, and our “further” (less related) alternative as a pogo or moon-kick (generating upward motion using limb momentum). Sticking to the primary alternative solution, I use a couple of tools:

- Require a first go on a moderate boulder using all active flag / smears, and a second go on the same boulder using all t-nuts, ensuring we carefully control (without being overly prescriptive) as closely as possible for which foot — and even where — they place it.

- Find a specific move with only one dominant foot, and have them climb it multiple times and change up the pattern of alternative use. For example, if they have six tries we might change the practice schedule depending on how good they are at it, with blocked practice probably being more prudent earlier in training and random more prudent later:

- Blocked Attempts: Flag, Flag, T-nut, T-nut, MED foot, MED foot

- Serial: Flag, T-nut, MED foot, Flag, T-nut, MED foot

- Random: Flag, MED foot, Flag, T-nut, T-nut, MED foot

Additionally, while shifting back-and-forth between complementary but alternative skill-sets, I may also randomize the order of skill-sets or participants for each boulder problem, sometimes by having them climb in pairs and playing rock-paper-scissors to see which skill-set goes first. Afterwards, I may randomize a more specific factor like t-nut / flag location.

Stage 2, Phase 3: Performance Representativeness Acclimation (re: Team-based training)

The third and final phase under the skill-adaptability training stage is called Team-based training, but for climbers its probably better to characterize it as an integration of your skill into higher-levels of performance representativeness. There should be more time spent in and around competition-style training with one caveat: coaches should be ever present to acclimate athletes to information sources necessary to incorporate their skills into actions. Their prime strategies are manipulating task constraints (the climbing, equipment, rules, etc.), and using instructional strategies of questioning and guided discovery. This phase is divided up into two types of activities:

Van Malkie, Bayes Wilder (Middle) and Matthew Baker (right) at US Youth Nationals. Bayes is on Team ABC, one of the top programs in the country. Recently, he’s begun working more specifically on drilling down into his specific movement needs and educating his attention more precisely to how he chooses to interact with the wall during a competition. Often times, he will call out a “skill” during team practice when he’s in a semi-chaotic and semi-pressured environment. Matthew and Van typify exceptional teammates who push one another in practice — creating a regularly competitive environment by which they attempt to integrate skills. Photos from Jason Chang (@theshortbeta)

First, repetition of situations that are goal- or target-focused;

- For example, more time in a t-nut specific environment, with numerous task goals designed around the use of t-nuts and pressure. For example, a 4-on, 4-off set of 4 boulders each designed with t-nut use, or a t-nut traverse competition to see who can climb it fastest with the only rule being the use of t-nuts, or a competition centered around getting points for the number of times an athlete can effectively use an upper-foot t-nut in under 1-minute, or a made-up boulder with a required t-nut placement, and seeing who can do it first.

Second, create task-specific and adaptable coordination patterns, constraining time, space, and numbers.

- For example, a series of 2-minute boulders built with t-nut use in mind (time constraint), placing tape over ideal t-nut placements (space constraint) during a t-nut focused competition (or even partially covering blocking t-nuts with tape), or changing up competition-associated numbers, like giving points for t-nut use (in addition to accomplishing a boulder) in order to gently encourage t-nut use during a competitive task (numbers constraint).

Stage 3: Performance Training

In this phase, skill development isn’t the primary focus. As a result, the goal should be to build up confidence in the athlete’s current abilities & training routines (e.g. warm-up, priming, between boulder routine, routine after the athlete turns around to look at the boulder, etc.)

Additionally, programming should start early enough out that a single skill like this doesn’t effect performance during the season, coaches should prep task rules with task complexity in mind, and they should consider making the overall stages (coordination –> skill adaptation –> performance) linear, while they block the different phases of skill adaptation (i.e. on any given week, all three phases may be used).

More Resources:

The Post Framework

Dr. Rob Gray’s Constraints led Approach (CLA) Resources

Dr. Rob Gray’s Differential Learning (DL) Resources