Research > Syntheses > “MOVESCI: Coaching Communication Loop”

The Coaching Communication Loop is an approach built by Dr. Nick Winkelman and highlighted in his book “The Language of Coaching” published through Human Kinetics in 2021. This approach builds off research and the author’s own background as head of athletic performance and science for the Irish Rugby Football Union and former director of education and training systems for EXOS’s NFL Combine Development Program. In a nutshell, Dr. Winkelman created a practical framework that directs attention, amplifies language, and reduces overthinking (cognitive load). The Coaching Communication Loop is a primer primarily meant for coaches but which may prove useful for self-driven athletes.

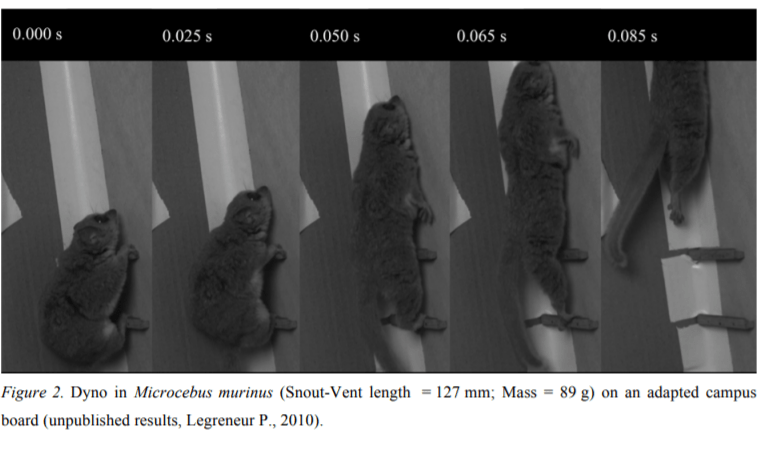

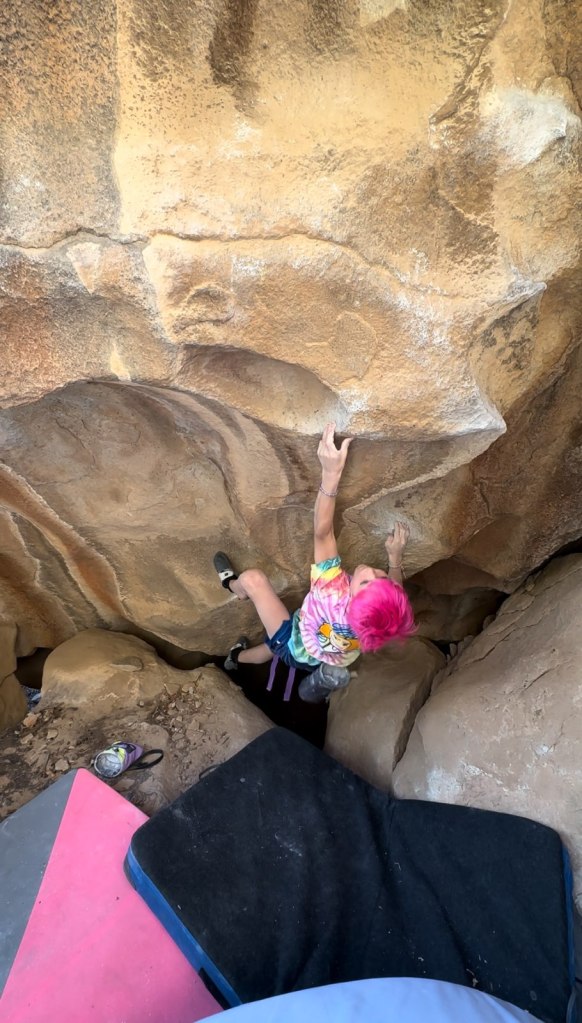

Dr. Winkelman advocates a Long Loop (DDCDD) and a Short Loop (the CDD of the Long Loop) for purposes of providing feedback to an athlete. Below, you’ll find an example of the DDCDD loop using a “lemur” as a model for a dyno. I have video of a lemur doing a dynamic jump move on an adapted campus board which Dr. Pierre Legreneur sent me (link to research below). The video is short and to the point, as is a comparison we use with French World Cup Climber Manu Cornu. For our purposes, I’ll post a picture (see above) as well as a human-example (see below).

This is why we say a picture is worth a thousand words and why coaches should endeavor to provide instructions, cues, and feedback that excite the theater of the mind.

Dr. Nick Winkelman

Here is a breakdown of the DDCDD loop using the lemur dyno as an example.

| Describe | I want you to dyno like a lemur. The lemur in this video does a hand-foot match, scrunches downwards but maintains a “suction-cup” like closeness to the wall. Then the lemur drives force hard through both the upper and lower holds by both throwing the top rung downwards and driving through the lower rung. | |

| Demonstrate | Try to imagine the still images below of a lemur on an adapted campus board are video. | |

| Cue | Cue Option 1: Scrunch up like a lemur and slide the wall! Cue Option 2: Smell the wall while you fly! Cue Option 3: Throw the top holds down like you’re trying to break a heavy bottle. Cue Option 4: Try to push the lower holds quickly and forcefully. Cue Option 5: Extend like a string bean. | |

| Do | Set up a tripod for video at the right angle (preferably to the side) to get a sense of the slide or stand so you can see the relevant features. You can use a short word or phrase at the right moment, like “Scrunch up!” or “Slide!” | |

| Debrief | “How close did you get to the wall?” “Pretty close.” “Did you get to the hold?” “Yeah, but I think I can get further. I felt like I extended really well but don’t remember whether I threw down well. Do you?” “Let’s focus on breaking the bottle this time. Throw the bottle down and smash it against the ground. I want coke to fly everywhere.” “So smash the bottle against the ground.” “Smash it.” “Got it, coach.” |

The nuggets that I’ve found particularly useful from Dr. Winkelman related to the loop:

- The cue should be “evocative” to the athlete. Meaning it should bring strong images, memories, or feelings to mind (Oxford Languages)

- The cues I used above are generic, and may work if you are pressed for time, but typically I like to allow the athlete to build their own representations and cues.

- The cue should be vibrant to the athlete. I often ask the athlete how they might represent — through a metaphor or analogy — what I’m asking them to do.

- Emotion may help strengthen the cue.

- Whether a cue is evocative to an athlete is based on finding something that stands out to an individual, or Salience. Dr. Winkelman highlights different kinds of salience, including relevance, intensity, frequency, and novelty. Additionally, these four can be influenced by positive and negative emotions, the current physical state, whether it aligns with an athlete’s goals/motives, and whether it is preceded by the athlete’s name.

- Working memory is finite, so timing your cue in relation to the attempt is important.

- Dr. Winkelman advocates “one cue per rep” although I try to hold back sometimes and cue after (or for) blocks of attempts and/or when requested.

- Similar body posture at the moment of hearing the cue may help recall at the moment of need, and potentially be aligned with the cue itself.

- The more effective cues may be less focused on ‘micro’ adjustments and more on ‘macro’ suggestions.

- Even when making a constructive criticism, frame the cue positively rather than negatively.

- Dr. Winkelman updates the External vs. Internal cue debate by creating a continuum of cues from narrow internal (specific muscle), broad internal (muscles around a joint, or entire limb), hybrid (partial body-focus, preferably ending with some targeted focus toward something on the wall), close external (the target of the cue is close to the body — like the hold you’re currently on), and far external (in climbing, likely a focus on trajectory or target hold).

Like a Twitter post, our memories seem to receive physical and emotional hashtags at encoding that can be used for later recall.

Dr. Nick Winkelman

In the future, I may do a write-up of other elements of Dr. Winkelman’s work such as his interpretation of Anders Ericsson’s deliberate practice model and his use of dials to represent — based on athlete need — increasing or decreasing (1) Process or Outcome Goals, (2) Explicit or Implicit Foci, (3) Feedback involving Knowledge of Results or Knowledge of Performance, and (4) the extent of the challenge (see Figure 2.2 on Page 30). For now, I’ll leave you with a small taste: on this last point (#4). Unlike the write-up on Dr. Wulf’s OPTIMAL theory where she suggests putting athletes through a Moderate difficulty where you err more toward success to work with an athlete’s motivation, Dr. Winkelman suggests that different levels of skill require different levels of task difficulty to learn appropriately (see figure 1.5 on Page 15). Please see the write-up on the POST framework for more on how (and what) to change in order to improve transfer and retention of learning.

While everyone’s working memory has a limited capacity, this varies across individuals. This explains why certain athletes can handle a lot of instruction with no negative effect on performance and learning, whereas other athletes cannot. Consequently, there is no replacement for getting to know your athletes and adapting your language to their limits — this is the art in the science.

Dr. Nick Winkelman

P.S. The Lemur dyno video is arguably the most effective dynamic movement teacher I’ve ever used, especially with the 6-10 year olds.

More Reading:

Dr. Nick Winkelman’s Coaching Communication Loop

Interview with Dr. Winkelman

A Framework for Coaching by Dr. Winkelman

Dr. Nick Winkelman’s “The Language of Coaching” book on Amazon

Lemur research link