Research > Syntheses > “MOVESCI: Adaptive Toolbox”

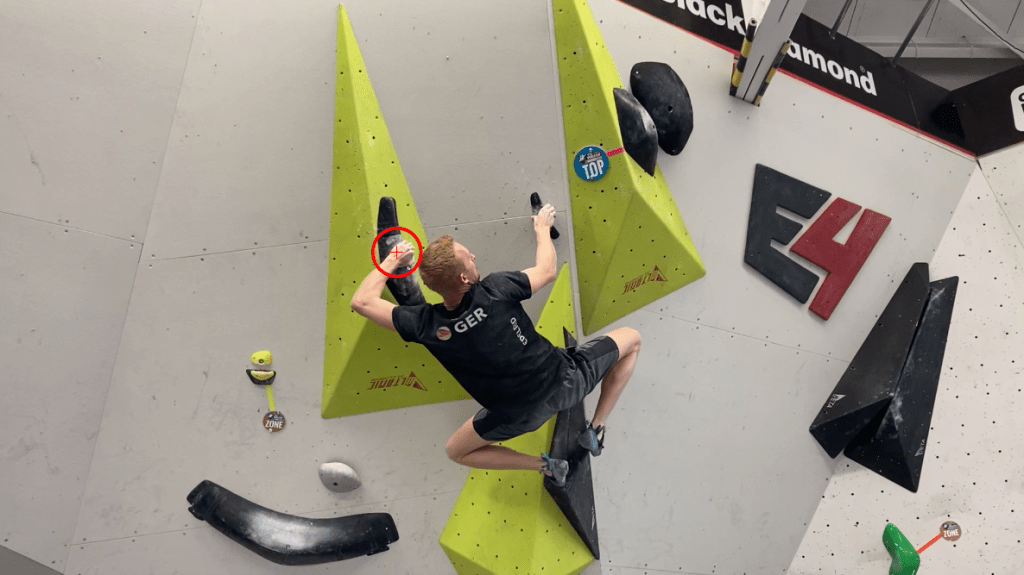

A collaboration between Dr. Patrick Matros (gimmekraft) and Taylor Reed. Featured image of Bayes Wilder.

The Adaptive Toolbox is an approach proposed by Oliveira, Lobinger, and Raab in 2014. Very simply, this approach attempts to build simple rules which are based on the right environmental situation. The authors argue that athletes create their simple decision-making rules (called heuristics) in a cost-effective manner, even if the rule itself is not necessarily the right rule for the situation. The Adaptive Toolbox falls more along the line of helping us understand decisions based on the environment, rather than in the pure execution of them.

There are four rule “types” — search rules, search-stopping rules, decision rules, and execution rules. Let’s take the example of “flagging.” A search rule looks for a foot to use as a base of support — called an information cue. Not finding one — or finding an unideal or “invalid” foot — the search instead looks for an alternative — the flag. The athlete can broaden or narrow the search depending on time and/or efficiency requirements, and potentially stop the search altogether and move onto a decision. Placing an athlete into a position that helps them search for information cues — as well as the validity of those cues — helps tackle the divide between perception and action.

Slightly more complicated, new rules will pop up based on refinement of the skill. For example, before the flag is made you may search for the ideal flag location — possibly based on your own internal understanding of how far the handhold is, or the texture of a potential foot, or even whether movement execution *may* cause your hips to jack-knife outwards during motion. This is sometimes called “nesting” because one rule is nested within another prior to execution.

A decision is made when recognition identifies the right information cue from the environment. The athlete doesn’t like their foot options. There’s no arete, so there is a flaggable surface. So they decide on a flag. Then execution has to occur based on past experience. There may be an overlap between decision and execution rules. For example, do they just flag passively? Is there an active “smearing” component to it, or does it pull away from the wall in an air flag? Is it a narrow flag or wide flag and how do those differ? Does it hop to different positions against the wall as the center-of-mass shifts upward? This may sound complicated, but only because we’re writing it out. The reality is that these are simple rules and usually happen without conscious thought (see OPTIMAL theory).

Athletes should be carefully placed into the situation to develop their information cues, as well as their alternative options. They should also learn when to rely on a small number of consistent heuristics and when to branch out to be creative with a larger number, involving more searches, stops, and decisions for a wider array of potential execution options.

Problem solving under pressure is the most important ability in a bouldering competition. Athletes have to “read” (analyze) the problem and to anticipate possible solutions. Afterwards, they put their ideas into practical attempts. It’s always tricky to find the sweet spot between believing in a decision you’ve made and keeping a flexible mind. For beginners there is this basic search rule: “Have I discovered every hold I can climb on?” Another very important, but much more difficult rule then is: “In which ways am I able to use these holds?” Sometimes elaborate heuristics reach their limits even in elite athletes. This is the time to re-“open the search stop rule door” again: additional tactile or kinesthetic information maybe helps to form a new “rule” for finally solving the problem.

An elaborated “shoulder move-rule with gaston” leads to failure, whereas a new “out of the box-rule with hand flip” leads to success.

One final example. Let’s take the heuristic: “keep your hips close to the wall.” We may call this a “principle” in climbing because it’s right most of the time, but can you say definitively when it is not right? A first group of you may be reading this and think that I’m asking a trick question: “It’s always right to keep your hips as close as possible to the wall.” A second group might think “it would be ideal, if I just had more mobility” — and they might be right or wrong. A third group might have been in situations where it just wasn’t ideal no matter how much mobility they had, but not know how to figure that out. And a fourth group may have good experience, a sense of their own external hip rotation, hip flexor capability, leg length, posterior chain strength, and spinal flexion, as well as a good sense of how foot orientation in relation to handhold inclination or depth may create the scenario whereby the hips are sacrificed in favor of something else. And a fifth group may say: “Forget that nonsense, I’m dynoing.” This last point is actually not in jest.

We could end this post by saying something like “Search, Stop, Decide, Act” but I don’t think that’s the cue we want you to take. Instead, we’ll say: Look for the environmental cues, and decide how valid they are for what you can do. Then see if you can make yourself use previously invalid cues if you think they may be valid with the right training. And we’ll leave you with a quote from the article on how to combine what we are good at, with what we need to work on:

We explore how athletes with different natural abilities (John and Mary) may become experts in their sport. John may have a natural ability to focus on a small number of cues and use those cues to maximal advantage. He will be identified as talented because of his consistent results in particular situations (rather than his creativity). During development, John may specialize in the use of those cues and become an expert in using them and hence build a narrow repertoire of expertise. Provided these are the most valid cues for the sports situation, John will also be an expert in his sport. If the sport offers a lot more variety, however, John will need to benefit from a varied training program that forces him to explore and use other cues for other situations. Mary, on the other hand, may have a natural ability to focus on a large number of cues and will therefore use various combinations of cues. She might be identified as talented because of her creative solutions (rather than her consistent results). During development, Mary may learn which cues are most valid to which situation and hence build a broad repertoire of expertise. Provided a number of cue combinations is required for the sports situation, Mary will also be an expert in her sport. If the sport offers little variety, however, Mary will need to benefit from a specialized training program that forces her to use the most valid cues.

More Reading: The Adaptive Toolbox